Communiqué Archive

Welcome to CAI’s blog archive. This lists past news items and stories about what has happened with the organization both stateside and overseas! Please send any comments or questions to info@ikat.org.

Welcome to CAI’s blog archive. This lists past news items and stories about what has happened with the organization both stateside and overseas! Please send any comments or questions to info@ikat.org.

December 23, 2013 – Getting it just right

One of the best ways to support women in rural and remote communities is to give them the tools to earn their own money.

“There’s a proverb, ‘Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime,’” said Central Asia Institute Co-founder Greg Mortenson. “The same thinking inspires CAI’s women’s vocational and literacy centers.”

CAI has more than 40 such centers, including 22 in the Gilgit-Hunza region of northern Pakistan, all aimed at women’s economic empowerment.

The centers are as different as the women themselves. Some focus on delicate embroidery for hats, pillows, and decorative items. Others make woolen thread and weave rugs. A few have started shredding old clothing into cotton stuffing and making bed mats. And many of them have evolved into tailoring shops, where members cut and stitch everything from school uniforms to men’s suits.

Yet all the women have one thing in common – a desire to sell their products and make money to help support their families. And as the centers have evolved over time, the committees that run them have increasingly asked for help marketing what they make.

To get some fresh ideas, Dilshad Begum, women’s empowerment director for CAI-Gilgit, organized displays of products at four handicrafts expos in and around Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital city, earlier this month. “I went to learn,” she said. “I wanted to see and experience the market situation, to advertise, see the demand value of the products made by CAI vocational centers, and see if we can find markets for the products.”

Ultimately, the goal is to continue to “empower and employ the well-trained women from the far-flung areas,” she said. But the work is evolutionary. “Each step takes time.”

CAI-G first worked with communities to build the centers. Next came skills training in embroidery, sewing and tailoring, weaving, and knitting. Then, as the women begin to generate cash for their goods, CAI-Gilgit helps them set up money-management systems and sort out the myriad issues that typically arise as the centers grow.

Time has shown that helping the centers requires a combination of social work and business management skills, along with hefty doses of patience.

Once the centers are established, the women increasingly find that they can produce much more than they can sell locally. A few centers have the connections necessary deliver items to market in Gilgit or Sost. And some of the centers have pooled their goods and opened roadside shops. But most of these areas are well off the beaten path and resources are scarce.

So Dilshad packed up a wide selection of handicrafts from the centers and, along with three trainers and two assistants, traveled to the capital to see and compare other products, observe trends, and assess the competition.

PAKISTAN MOUNTAIN FESTIVAL

The Pakistan Mountain Festival at the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) in Islamabad was a four-day event timed to coincide with International Mountain Day on Dec. 11. The goal of the festival was to give organizations working in Pakistan’s mountains a forum to showcase their work.

“Our products were highly welcomed by the students and teachers at the university,” Dilshad said. The event was short “but quite productive. It helped the team to interact with youth, and get feedback about the products and what changes they would want in future products.”

CREATIVE HAND CHRISTMAS GALA

The two-day “Creative Hand Christmas Gala” was held at the Islamabad Serena Hotel.

“Quite a number of guests visited [the booth] and we received appreciation from local and foreign tourists,” Dilshad said. “This event was a great success and helped our team to read the demand of the high-class society in the market.”

Fozia Naseer, CAI’s program manager in Azad Kashmir, also attended the Serena event along with Naseem Irshad, the teacher at the women’s vocational center in Bedhi village.

“The important thing for me was for our teacher to go there and see the things they make in the northern areas and get some ideas,” Naseer said. “I have always noticed that people, especially foreigners, like the smaller things. They want to buy something so they have a taste of the local culture, like a souvenir, but it should be small. Naseem was thinking she could sell some things, but a lot of them were too big, like the bed sets and sweaters, and you can’t always sell the big things.”

Naseem, however, was thrilled to see the possibilities.

“It was my first time to Islamabad after 16 years and I am really thankful to Central Asia Institute and to Fozia for the opportunity to see this,” she said. “It was a great experience. I wasn’t able to sell many things, people wanted different colors or patterns. But I learned a lot.”

FAMILY GALA

In Taxila–an ancient city about 20 miles northwest of Islamabad – the local Multi-Purpose Housing Society organized a three-day “family gala” that included a craft fair, Dilshad said.

“It was specifically targeted to mid-class society,” she said. “Although the days there were hectic, it helped the team to learn a lot about different markets and variety of products and their demands.”

MOUNTAIN FESTIVAL

CAI-G also set up a booth at the Lok Virsa, the National Institute of Folk and Traditional Heritage in the Islamabad’s Shakarparian Hills, during its early December Mountain Festival.

The one-day exhibition attracted people from different regions of Pakistan who “gave positive feedback about the CAI’s initiative to support women from the far-most regions of Pakistan in marketing and advertising their products,” Dilshad said.

“The team met many interested customers and provided them with samples of their products and they are expected to return with a larger demand,” she said.

The team’s efforts yielded a lot of information, which Dilshad will share with all the CAI-Gilgit centers in the months to come.

“It was tiring but it was a big success,” she said. “We learned a lot.”

Dilshad had help from CAI-Gilgit Office Manager Sayeed Akbar, Logistics Coordinator Munnir Uddin, and three trainers from the region: Jahan Bibi (Ghich), Afsana Bibi (Singal), and Sher Nigar (Hasis). Nasreen Gul, a CAI scholarship student studying nursing in Rawalpindi, also helped.

QUOTE: Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much. – Helen Keller

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications Director. Photos by Dilshad Begum and Fozia Naseer 2013.

December 19, 2013 – The 2014 Journey of Hope Calendars

The 2014 limited-edition Journey of Hope calendars are going fast!

If you want one – or more – act now to ensure you get a copy of this beautiful limited-edition collection of photographs from CAI projects in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan.

Each calendar is $10 and all proceeds go to CAI’s work to promote education, especially for girls, in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan.

To order online, click HERE. Or call 406.585.7841; email info@ikat.org, or send a note to: Central Asia Institute | P.O. Box 7209 | Bozeman, MT 59771, USA.

Thank you. Shukria. Tashakur.

- CAI staff

Sneak peek at what’s inside:

|

|

|

|

December 11, 2013 – CAI delivers another Journey of Hope

‘You can’t eat hope,’ the woman said.

‘You can’t eat it, but it sustains you,’ the colonel replied. – Gabriel

Garcia Márquez

WAKHAN CORRIDOR, Afghanistan – Central Asia Institute often talks about the “remote” places where we work.

We work in rural areas. We work in the mountains. We travel vertigo-inducing roads along mountain ridges and cliffs, through glacial streams, and over loose talus slopes to reach villages well off the beaten place, places where there is no electricity, cellphone service, potable water, paying jobs, or even a cash economy.

But I’ve learned that remoteness is a hard thing to convey to people who have never seen CAI’s work on the ground. As CAI’s communications director and the author of the annual Journey of Hope publication, I am constantly reaching for anecdotes to explain the isolation of these regions, and why working there is so rewarding.

For example, last year as I interviewed students in a ninth-grade class in De Ghulaman High School, I heard what sounded like a train (impossible, since the nearest rails are hundreds of miles distant) coming toward the school. Seconds later, a herd of yaks stampeded down the mountain, just outside the classroom windows – huge, burly animals, thundering toward the river. Their hoof beats shook the ground and drowned out voices in the classroom.

The students didn’t bat an eye. But I did. I glanced at photographer Erik Petersen and raised my eyebrows in response to the dream-like sight. It reminded me of something I read in Afghan Scene magazine. “The contrasts are sometimes what makes this place so hard to shake from the brain. There is surrealism to everyday life.”

As the herd thinned, a boy in threadbare clothes and plastic shoes ran behind it, herding strays.

That boy should be in school, I thought as the 15 students told me their dreams: four of them want to be teachers, two want to be engineers (including a girl), and eight want to be doctors. One girl had already resigned herself to the marriage her parents had arranged.

Just down the road, the ninth-grade students in Sheshp High School told me two of their female classmates had recently dropped out “because of marriage.”

“Girls usually marry at 14 to 16 years old,” Headmaster Bismullah said. “But their families [still] want them to learn how to live a better life, to have clean home and trade with animals and be better person.”

So the girls stayed in school as long as their parents allowed.

The remaining students, however, have high hopes amid almost impossible odds. Almost all of their parents are uneducated, with the exception of one boy’s father who studied to class three. “All are farmers, growing peas, wheat, and barley,” said Dehqan, 15.

The students’ awareness of their options is limited by their isolation. Not one of them has ever ridden in a car. Even though the traders who ply their wares up and down the only road through the Wakhan bring mobile phones to sell, there is no cellphone service to connect the village with the outside world. None of these kids have ever seen a television. “Once upon a time a man had a television and everyone wanted to see it, but it didn’t work,” Dehqan said.

The children’s off-school hours are filled with work. They rise with the sun to look after the sheep, milk the cows, and bring the water from the spring. After school they collect firewood and pound animal dung into patties for heating and cooking fuel, wash the dishes, and tend to the younger children.

But they have dreams. One girl, Moina, said she wants to go to high school and then to university. “I want to study because I want to be a doctor. There are no doctors here.”

“These children are the future,” says CAI Co-Founder Greg Mortenson. “But their lives are hard.”

Across the Panj (Oxus) River, in Tajikistan’s rural and mountainous Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast, it’s common to see children on the roadside selling fresh and dried fruit, recycled plastic jars filled with honey, or bags of nuts to supplement their families’ meager incomes. They try to flag down drivers or run alongside slow-moving vehicles.

In urban areas, young children fare no better. They work for “small money” in shops, as mechanics, or even factories – anything to help keep the family alive. They join their mothers begging at busy intersections or on the muddy side streets. They dig through trash piles in search of food, or anything they can burn as fuel.

Children’s poverty haunts everyone. But the good news is that there is a growing acknowledgement that education is the path out of poverty.

“Education is a matter of life and death for us,” Mohammad Hanifa, a 15-year-old in class nine at Sun Valley High School in Khanday, Pakistan, said in a speech at an all-school assembly in June. “We all know the importance of education. Without education any nation cannot progress. The world is progressing rapidly [and] without requisite advance in education not only shall we be left behind others, but we may be wiped out altogether. Our Holy Prophet also said that ‘seeking knowledge is the duty of every Muslim man and woman.’ The importance of education is equal for men and women both. We [are] especially thankful to [Central Asia Institute] who provide us with the opportunity to get the quality education.”

He then asked CAI to please help his school construct a science laboratory for the upper-class students. “Our future is in danger,” he said.

Mohammad was not exaggerating. And his ominous plea applies across the regions where CAI works.

“Until the last decade, many people in Afghanistan lived in such isolation that they were largely untouched by the modern world,” according to the 2010 Afghanistan Education Sector Analysis by London-based Adam Smith International. “Reliance on subsistence farming as the primary means of livelihood for over 90 percent of the country further entrenched the insularity of much of the population. Except for a very few urban areas, many communities had little contact with trading or commercial centers. Accordingly, in many parts of the country, neither men nor women had access to formal educational opportunities.”

Girls, especially, suffer. In many areas where CAI works, female literacy rates are still in the single digits. In conservative areas, girls who pursue education still face threats from extremists, family opposition to girls’ education, and being forced into marriage. Others have no options: In Urozogan province, for example, there is no high school for girls.

“Afghans, as is true in many low-income countries, typically invest less in the education of their daughters than in that of their sons,” according to the Smith analysis. “It is understood that boys will grow up and continue to support their parents. Daughters, on the other hands, are often seen as having a low investment potential, since they will join their husband’s family as soon as they are married.”

But there is hope. Our annual Journey of Hope publication – which will be mailed in coming days – documents CAI’s centers of hope, which now include nearly 300 schools, 42 women’s literacy and vocational centers, 10 scholarship programs, and 31 public health (potable water, midwifery, and disaster-relief) projects.

This is the seventh edition of Journey of Hope, which is, for me, seven labors of love. Since my first trip to visit CAI projects in 2007, I have returned 18 times and visited hundreds of projects. In many of these areas, the poverty is profound. Malnutrition, opium addiction, and disease are often too prevalent for my Western, solution-minded disposition. The rising sectarian violence and the war with extremists, both of which have crept into once-peaceful remote areas where CAI has projects, take a toll on everyone.

But the kind of work that CAI does in the world takes time. Mortenson often says it takes generations. And it is happening, as the late CAI proponent Sarfraz Khan used to say, “Slowly, slowly.”

Questions about the future abound – not the least of which is what will happen when international security forces leave Afghanistan at the end of 2014. In Pakistan, the “permanent state of enmity with India,” combined with a desire to influence what happens in Afghanistan, and deploy “Islamic extremists or non-state actors as a tool of foreign policy in the region,” continues to drain the national budget, author Ahmad Rashid wrote in a New York Times op-ed in 2011. “Democracy, liberalism, tolerance, and women’s rights … are all pronounced Western or American concepts and dismissed.”

“Pakistanis desperately need a new narrative,” he wrote. “But where is the leadership to tell this story? … Nobody is offering an alternative.”

Can hope survive and prevail against such a backdrop? Of course it can and it will. We have to dream. And we have to encourage the children to dream.

“There are 600 million adolescent girls in the world today, imagine if they were educated to the point where they were economically viable, where we can make sure they can exercise their rights, where we can make sure they will not be abused,” UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin said in May 2013. “We would have a peaceful world because women are peacemakers, because women build nations.”

At CAI, it is our job to help as many of those girls – and boys — as we possibly can get a quality education and fulfill their dreams for a better future.

As the author Barbara Kingsolver wrote: “The very least you can do in your life is figure out what you hope for. And the most you can do is live inside that hope. Not admire it from a distance, but live right in it, under its roof.”

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director.

At this time of year, when days are short and the dark nights seem so long, it is important to remember the light in our lives. Remember the joy.

In the words of Frederich Buechner: “Joy is a mystery because it can happen anywhere, anytime, even under the most unpromising circumstances, even in the midst of suffering, with tears in its eyes.”

Joy is a mystery. And it is a gift.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director. Photos by Erik Petersen

December 3, 2013 – Be a part of Giving Tuesday. It will make a difference.

As Central Asia Institute’s database manager, I am the lucky person who sees the generosity and thoughtfulness of our supporters every day. I hear and read CAI supporters’ stories about why they are passionate about girls’ education and peace in the communities where we work. I receive the handcrafted cards from Florence in Washington each month. I read letters from motivated teenagers like Amy in Massachusetts, who grew up volunteering for her father’s non-profit. I am humbled to hear from young students who donate their birthday money to support Pennies for Peace.

It is inspiring that so many people take the time out of their busy lives to give. Give their time, compassion, and money to support CAI’s mission in Central Asia. We at CAI are thankful for our supporters – thank you for giving, and helping create a better world for so many.

Thanksgiving is a time to give, be thankful, and spend time with family and friends. But it has also turned into a time of consumption and materialism. Black Friday now starts on Thanksgiving Day, and for some, the whole holiday is centered on shopping.

Last year, Giving Tuesday was started to create a day of giving that follows Black Friday and Cyber Monday. The idea is to inspire people to give to their cause of choice. Today is Giving Tuesday and we want you to be a part of it.

Donations to CAI go toward supporting community-based projects in remote areas of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan. If you did shop on Black Friday, the money you saved could send a girl to university, or provide clean drinking water for an entire community. Giving just a little this Giving Tuesday could be the first step toward educating a girl, and empowering a community.

If you can’t donate today, you can still give – volunteer, start a Pennies for Peace drive, or post an #UNselfie to promote Giving Tuesday. Give back to the world around you in some way today. It will make a difference.

To donate to CAI, click here.

For more information on Giving Tuesday, visit www.givingtuesday.org.

QUOTE: We only have what we give. – Isabel Allende

- Laura Brin, CAI’s database manager

November 27, 2013 – Attitude of Gratitude

Thanksgiving is a national holiday in the United States that dates back to colonial times, a time to count our blessings and express our thanks.

It was the first U.S. president, George Washington, who proclaimed in 1789 that “it is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor.”

Nearly 70 years later, as the American Civil War raged on, then-President Abraham Lincoln set aside the final Thursday in November as a national Thanksgiving Day. In a 1863 proclamation, Lincoln urged Americans to give thanks for their numerous blessings, remember the “widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged,” and pray to God “to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it [to] … peace, harmony, tranquility and union.”

In recent years, the holiday has evolved into a more secular celebration for many Americans, complete with football games, parade, and lavish family dinners. Yet it remains centered around gratitude.

With all that in mind, we at Central Asia Institute have been reflecting on what we’re grateful for. Throughout November we have posted those reflections on our Facebook page (click to see those posts, along with photos and supporters’ comments and contributions to the conversation). But here are the highlights:

• We’re grateful for the determined children learning to read and write in CAI-supported

schools.

• We’re grateful for small donkeys, those beasts of burden that help carry the load for children and

adults throughout the mountains of Pakistan, Afghanistan, & Tajikistan.

• CAI is grateful for friends, those people who stick with us through thick & thin, make us laugh,

hold our hands, and know our hearts.

• We are especially grateful for teachers, those patient and persistent people who educate, encourage,

and inspire us. They teach us to think. And they light up the world.

• We are grateful for music, the language that goes beyond words, that touches us in ways nothing else

can. Music inspires, comforts, calms, enthralls, and connects us. And it makes us want to dance.

• And we are thankful for mountains. As Jill Wheeler said, “Mountains have a way of humbling us, if we

accept the opportunity. Mountains have a way of connecting us to ourselves, nature and to others, by

simply being out there. Mountains have a way of challenging us so we learn we can handle more, achieve

more and feel stronger.”

We are also grateful for our supporters, people who believe every child should learn to read and write, and who believe in the power of education to change the world.

Thank you, tashakur, shukria.

Happy Thanksgiving to one and all.

QUOTE: In normal life we hardly realize how much more we receive than we give, and life cannot be rich without such gratitude. It is so easy to overestimate the importance of our own achievements compared with what we owe to the help of others. – Dietrich Bonhoeffer

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director

November 15, 2013 – Difficult and dangerous: Education in Afghanistan

EDITOR’S NOTE: David Starnes recently returned from his first visit to Afghanistan as Central Asia Institute’s executive director, a position he has held since March 2013. Here he shares some of his thoughts, impressions, and reflections.

A lasting impression from my recent visit to Afghanistan was inspiration: from those who built these schools and the students who continue to endure great hardship to attend the schools and receive an education.

One striking example of this came during my visit to a CAI-supported school south of Kabul (the exact location cannot be disclosed due to safety and security reasons). The school had been badly damaged by a truck bomb that exploded nearby. The explosion left behind shattered windows and damaged doorways, a reminder of the extent to which violence is still prevalent in the areas where we work.

|

|

|

|

The school was closed until the repairs could be made; however, since all schools in Afghanistan become the property of the Afghan government, it is still unknown how long it will be until the students return.

While we toured the school, gunfire erupted near us. We were standing in the front entrance area when the bang of rifles and staccato of automatic weapons echoed around the area — most likely a gun battle between police and militants.

We left the village and drove to another CAI school atop a hill, overlooking the community we had just left. This time, students were present and talked to us about their school. We asked them about the fighting in the area, and they freely shared that fighting occurred almost daily and that it was common for stray bullets to strike the school. When asked if that scared them, they shrugged and said it is the way things are. It is simply part of the risk that they take to come to their school.

Many of us take our education in the United States for granted, but in Afghanistan, many students have to fight for the right to a basic education. Some students are forced to earn their way to be allowed to attend school. Others have to overcome violence and neglect. Still others are forced to adopt basic survival skills in the war zones that they call home. But they do all of those things because they value literacy and knowledge. They are willing to put their lives on the line to receive their education.

- David Starnes, CAI’s executive director

November 13, 2013 – “Sir Sarfraz”

A year ago today we lost our dear friend and colleague Sarfraz Khan. There are no words to express how much we miss him, his sense of humor, his energy, and his tireless determination to help CAI make the world a better place. We think about him every single day.

On this day, we’d like to honor his memory by sharing a poem written by several CAI-supported scholarship students in northern Pakistan. These young women read the poem aloud during a ceremony in Gilgit, Pakistan, in May.

Sir Sarfraz

The moment when the lamp extinguished

The earth wept. The skies cried.

The earth has since been weeping.

The sky has since been crying.

If we were asked to make a wish,

The wish would be to have you back.

Our eyes full of fear, our hearts thumping fast

We have left our worries in the past

And there’s nothing to fear

But why we are so scared?

Life shattered in front of us

Dreams scattered on the floor

All the hopes and dreams we had with you

Have no meaning any more

We have lost ourselves, deep taken in, by all the sorry

In the unfathomable oceans of woes

We walked towards the beacon

But it dimmed and going to be our

It again shone

We wanted to get caught

But it was gone.

We are the glamour of today

Our life complete cessation

But your glimmering guidance endless

And your shining star ceaseless

Akin sweet temptation

Indeed your guidance endless

Moments that we spend together

Your love was so warm, like a father

But never forget you, ever and ever

So hard to find, a devotee as you

Little drops of water, rolling down our face

Full of deep emotions, extreme pain their base

We try our best not to cry

But they fertile the soul, that is so dry.

Our silence inside us engulfs us like a bug

Our injured esteem, hurts with people’s tug.

He is popular

He is a flower of heaven

He is lighting our lives

Such a great person

God has gifted you a wisdom

We love you.

The way of education you have shown.

You have shown us right path.

You are a loyal

You are the crown of our heads.

You have given a good chance to get the education.”

Composed by: Shabana Jabeen, Ghazala Naz, Naila Jabeen, Naseem Bari & Rahima Naz

- Compiled by Karin Ronnow / Photos by Ellen Jaskol

November 8, 2013 – CAI Releases Annual Report (September 30, 2012)

Central Asia Institute (CAI) has released the Annual Report for the fiscal years ended September 30, 2012 and 2011. The report summarizes CAI’s financial statements and programs, and illustrates how your support continues to further our mission.

As I noted in my annual report message, I am just settling back into my office in Bozeman, Montana, after a four-week tour of Afghanistan, where I made extensive visits to schools, women’s centers, and community-based projects. This trip came on the heels of my June trip with Greg Mortenson to Central Asia Institute (CAI)-supported schools and projects in Pakistan.

The scope and scale of CAI’s work in some of the most remote and dangerous areas of the world is inspiring. Schools that were originally started years ago with 20 or 30 students now have hundreds of students. Young girls, who 10 years ago were prevented from attending schools, now make up the majority of students in many schools. We are honored and proud that, with your support, CAI delivers hope to children, women, and their families in underserved areas of Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan.

The past two years have been a time of controversy, change, and transition for CAI. While continuing to support hundreds of schools and projects overseas, CAI staff and volunteers have worked tirelessly to improve CAI’s operations and procedures to ensure that the wishes, intents, and trust of our donors and the best interests of our beneficiaries are our highest priority. Just a few highlights include:

1. CAI has completed all actions required under the Agreement of Voluntary Compliance—a document signed by CAI and the Montana Attorney General’s Office in 2012 that outlined corrective measures and monitoring procedures.

2. Expansion of our Overseas Grantee Monitoring program, with independent accountants now reviewing CAI-funded projects and grantees’ activities in all three countries.

3. Completion of the independent financial audit for the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2012.

4. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s decision to dismiss with prejudice a lawsuit claiming damages against CAI and Greg Mortenson over Three Cups of Tea.

Looking ahead, CAI will continue to focus on sustainability and improving the quality of CAI-supported schools and projects through teacher trainings, scholarships, curriculum enhancement, provision of school supplies, and expanded training for community health workers. While that means fewer new schools in the near future, it reflects a commitment to an improved educational experience for all students. Like you, we want to insure that the young girls and boys we serve will live out their dream of getting an education—and that they can go on to become the next generation of locally educated doctors, teachers, nurses, accountants, agriculturalists, engineers, lawyers, pilots, policewomen, professors, and more.

On behalf of CAI’s Board of Directors, staff, and the communities we serve, thank you for your continued dedication to the mission of peace through education.

- David Starnes, CAI’s Executive Director

CAI’s Annual Report and the full audited financial statements are also provided on our Financials Page.

November 6, 2013 – 2014 Journey of Hope calendars available for pre-orders

The 2014 limited-edition Journey of Hope calendar has gone to press and Central Asia Institute is now taking preorders.

This year, photographer Erik Petersen and CAI Communications Director Karin Ronnow documented CAI projects in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. The calendar includes stunning photography of CAI projects, plus explanations of CAI’s programs and a map of the areas we serve.

The stories will be published in the upcoming “Journey of Hope,” which is scheduled for an early December distribution.

Each calendar is $10, with delivery available by early December.

Proceeds from all calendar sales help CAI carry out its mission to promote and support community-based education, especially for girls, in remote regions of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan.

Order yours now. CAI calendars make great gifts, and help us spread the message of peace through education.

To order online, click HERE. Or call 406.585.7841; email info@ikat.org, or send a note to: Central Asia Institute | P.O. Box 7209 | Bozeman, MT 59771, USA.

As always, thanks for your support.

- CAI staff

Sneak peek at what’s inside:

|

|

|

|

November 5, 2013: Happy Islamic New Year!

Central Asia Institute wishes everyone a blessed Al Hijra (Islamic New Year)!

Al Hijra is the first day of the Islamic New Year. It marks the day when Mohammad began his migration from Mecca to Medina to establish the first Islamic state in Islamic Year 1 (AD 622).

For Muslims, the New Year is not a holiday with a lot of traditions or rituals, although some individuals make resolutions and use it as a time of self-reflection.

“We seek forgiveness on shortcomings of the past,” Imam Shamsi Ali of the Islamic Cultural Center of New York, the city’s largest mosque, told odysseynetworks.org. “And we are being thankful for the good we already achieved or obtained in the past. At the same time, we are putting our new visions and renewed commitment to do better in our coming days.”

Not everyone agrees on the precise date for Al Hijra, as the Islamic lunar calendar typically has several variations by region.

Like the Gregorian calendar, the Islamic calendar consists of 12 months, according to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England. However, each month starts with the sighting of the crescent moon and is 29.5 days long. The Islamic calendar year, then, is 354 days long, 11.25 fewer days than a Gregorian calendar year.

This year’s holiday marks the start of the year 1435.

Many Islamic countries, including Afghanistan and Pakistan, use the Islamic calendar alongside the Gregorian calendar. Muslims everywhere use it to determine the proper days on which to observe the annual fast of Ramadan, attend Hajj and celebrate other Islamic holidays.

QUOTE: We will open the book. Its pages are blank. We are going to put words on them ourselves. The book is called Opportunity and its first chapter is New Year’s Day. – Edith Lovejoy Pierce

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director

October 15, 2013: CAI humanitarian support safely delivered to Eskitol village in

Afghanistan

After waiting weeks for the fighting to abate, a Central Asia Institute team has safely delivered a truckload of humanitarian aid to a small mountain village in northeast Afghanistan that was buried by a landslide in September.

Five people were killed when heavy rains triggered the massive slide, sending boulders, rocks, dirt, and mud down the mountainside onto Eskitol village in Badakhshan province, said Janagha Jaheed, one of CAI’s Afghan community program managers. The landslide also destroyed homes, fields, bridges, and roads.

“The people, especially the women, were very much happy about receiving the support and said CAI is the first organization that could reach them and get into this remote area,” Jaheed said. “They particularly mentioned that the food package and tents and blankets they received are very helpful because they have lost their houses and all tools. Also the weather here is getting cold and the women and children were getting sick and suffering due to being out in the open space and having no good food.”

CAI learned of the disaster from Jaheed, who e-mailed the Bozeman office. “A mountain slide started over Eskitol village at 9 o’clock at night and continued until 9 o’clock the next morning,” he wrote. “As result of this phenomenon, five people were found dead, but 15 more are still not found.

“Forty houses are totally eliminated,” Jaheed wrote. “More than 300 goats, sheep and cows of the local people have been killed, 900 bags of cement from the National Solidarity Program are also lost and almost 100 acres of land … is changed to flood field and has become useless. The power station of the village is also eliminated; three bridges are totally destroyed; and the road to Eskitol remote village is cut. Those who are alive have been carried to an open and wide dessert.”

CAI does not have a school in Eskitol, although village leaders have requested one. Those same leaders helped us in 2010, when CAI built a school in nearby Sangliche, “one of the most remote and isolated villages of Zebak district, just about 20 kilometers to Pakistan border,” Jaheed said. Nimatullah, an Eskitol elder, helped with preparations and logistics for the CAI team’s journey, collecting 12 donkeys to carry people, building and school supplies, “a real journey of hope,” he said.

Now Nimatullah and his extended family are homeless, Jaheed said. So much “has gone under the flood and is lost,” he said. “They are in a very bad condition.”

Zebak District Education Director Abdul Majeed Khan was the first government official to cross the river and visit the disaster area. He told Jaheed about the situation with the local school: “They had a small area with three tents set up as a primary school, but the flood and landslide, unfortunately, have completely removed the field and tents. As the phenomena started at night and students were not at school, no student has been killed there. But right now not only students, but all children need urgent help and aid like food and clothes.”

Delivering aid was to the beleaguered villagers was complicated by fighting between Afghan forces and the Taliban in Warduj district, adjacent to Zebak.

But the CAI team made it to Eskitol with a truckload of tents, blankets, and food on Oct. 2. Jumah Gul, CAI field manager in Zebak, and Mahbobullah, administrative/finance officer in Baharak, led the disaster relief delivery effort.

“It took place in the time when Taliban were all around the mountains of Eskitol village and there was much security risks in the area while our team was getting in there, according to Zebak district Gov. Mir Ahmad Shah Zigham,” Jaheed said. “But they did not stop. They got there and did their noble job.”

Each family received a tent, blanket, and a package of food that included flour, rice, oil, tea, and sugar.

QUOTE: What is the use of living, if it not be to strive for noble causes and to make this muddled world a better place for those who will live in it after we are gone? – Winston Churchill

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director

October 11, 2013: International Day of the Girl Child

The United Nations General Assembly adopted a Resolution in 2011 setting aside October 11 as the International Day of the Girl Child. The intent is to call attention to girls’ rights and the unique challenges girls face around the world.

Today, during this second annual celebration, the focus is on “Innovating for Girls’ Education”.

As the UN noted, girls’ education “is the one consistent positive determinant of practically every desired development outcome.” Yet, as the UN also noted, “many girls, particularly the most marginalized, continue to be deprived of this basic right.”

Central Asia Institute joins people around the world in honoring girls as we continue to work for the right of every child to get an education and pursue her dreams.

Help us spread the word by sharing our post on Facebook or Twitter.

- Central Asia Institute

October 9, 2013: Federal appeals court affirms dismissal of case against CAI and

Mortenson

BOZEMAN, Mont. – Central Asia Institute was pleased to learn Wednesday that the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco has dismissed the purported class-action lawsuit against it and CAI Cofounder Greg Mortenson.

The federal appeals court ruling upholds U.S. District Court Judge Sam E. Haddon’s dismissal of the case with prejudice in Great Falls, Mont., in May 2012.

A three-judge appeals panel ruled that the plaintiffs’ “conclusory statements and minimal factual allegations” on the allegations of fraud, deceit, racketeering, or breach of contract were vague and insufficient, according to court documents.

Also, “the [lower] court acted within its discretion in dismissing the complaint and denying leave to amend. Plaintiffs have already had multiple opportunities to amend, even after the defects in the pleadings were identified in extensive briefing[s].”

U.S. Appeals Court Judges Barry G. Silverman, William A. Fletcher, and Consuelo Maria Callahan unanimously agreed the case was “suitable for decision without oral argument” and concluded: “The district court properly dismissed the complaint.”

“Clearly I’m pleased with the court’s decision,” said CAI Board Chairman Steve Barrett. “I’m also happy to report that we have satisfactorily completed all specific actions outlined in the Assurance of Voluntary Compliance that CAI signed with the Montana Attorney General’s office in 2012.”

The AVC was part of a 2012 settlement agreement following the AG’s inquiry into allegations that CAI had, over a period of years, failed to maintain adequate financial controls, governance, and stewardship processes. CAI has since made numerous internal changes. The AG’s office has indicated it is satisfied and did not propose any action beyond those enumerated in the AVC.

“The conclusion of both of these weighty matters – the appeal and the AVC requirements – allows CAI to rededicate its energy and resources to the important work of promoting education, especially for girls, in remote areas of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. As we’ve said before, no other NGO does what we do in these locales with such a small team of dedicated individuals.”

CAI has worked with communities in these mountainous regions for 17 years to build and/or support nearly 300 schools, 42 women’s literacy and vocational centers, 10 scholarship programs, 31 public health (potable water, midwifery, and disaster-relief) projects, and more than a dozen community programs.

Click here to see the ruling on the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

CAI staff is available to answer any questions or concerns. Please contact us at info@ikat.org.

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director

October 7, 2013: Students express hope & gratitude during “Dr. Greg’s” visit to

Baltistan

Central Asia Institute Cofounder Greg Mortenson just wrapped up his second visit to Baltistan, in Northern Pakistan, this year to visit schools, students, teachers, and old friends.

Accompanied by Mohammad Nazir, our community project manager in Baltistan, and a small crew of CAI supporters and volunteers, he spent three weeks traveling the back roads of Baltistan. He visited some of CAI’s oldest projects in the Shigar, Braldu, and Hushe valleys, and met with leaders in communities seeking CAI’s help with education for the first time.

Asked about his impressions, he offered this quote from Edward Kennedy: “The work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dreams shall never die.”

Here are some photos from Greg’s September education expedition. We hope you find them as inspiring as we do.

“More powerful than politicians, bombs, drones, armies or

terrorists: first-grade schoolgirls,” Greg Mortenson says of these students at

Jafarabad Girls’ School. Photo: Mohammad Nazir, 2013.

|

Greg Mortenson and Taha Ali, village chief in Korphe, visit

with schoolgirls in Shigar Valley, Baltistan. These are the first girls in their

village to ever attend school. Photo: Mohammad Nazir, 2013.

|

“Girls’ education is the most powerful force of change in the

world,” says CAI cofounder Greg Mortenson. Photo: Greg Mortenson, 2013.

|

Hyderabad Middle School students and teachers gather for the

inauguration of the recently expanded school. Photo: Mohammad Nazir, 2013.

|

This fifth-grade girl (wearing a black cape) wants to be the

first policewoman in the Shigar Valley, Baltistan, Pakistan. Photo: Mohammad Nazir,

2013.

|

Greg Mortenson reviews a biology lesson on blood flow through

the human heart with a seventh-grader. Photo: Mohammad Nazir, 2013.

|

Students at Nar School in Baltistan, Pakistan, gather outside

their classrooms for a group photo. Photo: Greg Mortenson, 2013.

|

Hushe students crowd into school veranda while storm passes.

Photo: Mohammad Nazir, 2013.

|

Sakina back in Korphe village after heart surgery in Italy.

Photo: Mohammad Nazir, 2013.

|

Greg Mortenson with Jafarabad Girls’ School students. “Brave

girls full of hope,” he said. Photo: Mohammad Nazir, 2013.

|

Thugmo village schoolgirls enjoy a “drama” (play) at their

school in September. Thugmo is in the Shigar River valley north of Skardu. Photo:

Greg Mortenson, 2013.

|

Students at Nar School in Baltistan, Pakistan, gather outside

their classrooms for a group photo. Photo: Greg Mortenson, 2013.

|

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director

September 16, 2013: Australian quilter captures hope through education

Photos speak to people in unanticipated ways. Because they have the power to reach beyond words to tell a story, photographs can provoke emotion and create connections. And they can inspire.

Ellen Jaskol’s photos in Central Asia Institute’s (CAI) 2012 “Journey of Hope” calendar so inspired artist Gillian Shearer of Australia that she replicated one in an art quilt.

“I enjoy creating art quilts of people, especially children,” Gillian wrote to Ellen in an email, asking permission to use a particular photo. “I love all of the images you took from your time there and it was hard to pick just one.”

The one she chose was the calendar cover photo of two schoolgirls, an image Ellen captured in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor in September 2011.

“I am so touched that Gillian chose to do a quilt from this photo of the two schoolgirls,” Ellen said. “Of all the thousands of photos I’ve made of Afghanistan and Pakistan, I think she picked my absolute favorite image.”

After getting Ellen’s permission, Gillian stitched the 125-by-83-centimeter quilt entitled “If You Educate a Girl You Educate a Village,” with the intent of entering it in an Australian quilting contest this fall.

Gillian’s use of vibrant colors juxtaposed with shadows, the lifelike hair, fingers and toes, and the determination depicted in the young girl’s eyes convey the power of education to inspire hope.

“I lost count of how many hours it took in the end, and how many tiny pieces of fabric it took to make the girls!” she wrote. “It’s been one of the most tedious quilts I’ve made but certainly one I’ve had the most joy in creating.

“I’ve had lots of nice comments and really enjoy explaining the story behind it,” she added. “I hope I did it justice.”

We think she did a terrific job. Or, as Ellen said, “Wow!”

Good luck in the Queensland Quilters competition, Gillian.

QUOTE: If you could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint. – Edward Hopper

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director

September 3, 2013: Pashtun women’s poems reveal centuries of irrepressible creativity

Afghans hold poetry in high regard. But if you want a glimpse into the private lives of mostly illiterate Pashtun women, get your hands on a copy of Poetry Magazine’s June issue. It is dedicated to landays, the two-line, 22-syllable Pashto poems of life and death, love and war, laughter and loss.

“This is rural folk poetry,” Eliza Griswold, a journalist and poet who worked with photographer Seamus Murphy to collect the landays and share them with an international audience, said in an interview on PBS’ News Hour.

Many landays reflect painful realities of Pashtun women’s lives:

“When sisters sit together, they always praise their brothers.

When brothers sit together, they sell their sisters to others.”

“You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.”

Others have a modern twist, Griswold noted. “Women have recited these poems for centuries,” she told PBS. “So they have gone from talking about the riverbank, which is the place you gather water – and, of course, the place men go to spy on the women they have crushes on – to Facebook, to the Internet. And so they really reflect the currents that women in Afghanistan are encountering today.”

“How much simpler can love be?

Let’s get engaged now. Text me.”

The couplets are passed along orally, often to music, and in some cases for generations. “This is poetry that’s meant to be oral. It’s passed mouth to mouth, ear to ear,” Griswold said.

The result is that landays “belong to no one and everyone,” Murphy wrote in an essay on the project.

But they are also anonymous, to protect the female poets, who risk their lives to write, sing, and share the poems. Griswold actually got the idea for this project after she wrote a magazine article about a young woman who’d been beaten for writing poems and later killed herself.

Murphy recalled: “A group of women from Helmand discussing landays in a refugee camp insisted on burying Eliza’s mobile phone in a sea of cushions to ensure no recording could be made of their voices. They didn’t want recognition. They said they could be murdered if their husbands knew what they were discussing with outsiders. The significance of this separates our worlds.”

Yet the two were determined to collect and translate the poems before international forces leave the country in 2014. With the help of a Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting grant, they made several trips to Afghanistan and women and girls singing the landays in their homes, at weddings, in refugee camps.

“Pull that burka back, and [a Pashtun woman] will talk to you about the size of her husband’s manhood,” Griswold told PBS. “She will go right for it: sex, raunch, kissing, rage. She will talk about the rage of what it is to be cast in this role of subservient, in a way that’s really startling.”

“Your eyes aren’t eyes, they’re bees

I find no cure for their sting.”

“I could have tasted death for a taste of your tongue,

watching you eat ice cream when we were young.”

Murphy wrote that the poems helped him to understand the strength of Afghan women: “I discovered landay poetry through the book, “Songs of Love and War,” a collection sourced and edited by the eminent Afghan poet and philosopher Sayd Bahodine Majrouh. Landays were couplets that had the ache and anger of simple truth. They barely or rarely mentioned God and left me feeling I was being profoundly changed. That they reportedly came from mostly illiterate Pashtun women leading oppressive lives in rural areas made them even more remarkable. A hidden world opened up; it was like rediscovering Afghanistan.”

The structure of the poems is always, in Pashto, two lines and 22 syllables: nine syllables in the first line and 13 in the second, Griswold wrote in the introduction to the collection.

“Sometimes they rhyme, but more often not. In Pashto, they lilt from word to word in a kind of two-line lullaby that belies the sharpness of their content, which is distinctive not only for its beauty, bawdiness, and wit, but also for the piercing ability to articulate a common truth about war, separation, homeland, grief or love.”

“I call, you’re a stone.

One day you’ll look and I’ll be gone.”

“Be black with gunpowder or blood red,

but don’t come home whole and disgrace my bed.”

The poems also offer a unique insight into how the women view the war.

“There’s a lot of anger at the Taliban, a lot of rage at the hypocrisy of the Taliban, and an equal amount, if not more, rage at the hypocrisy of the Americans and what their influence has left behind,” Griswold told PBS.

“May God destroy the Taliban and end their wars.

They’ve made Afghan women widows and whores.”

“My Nabi was shot down by a drone.

May God destroy your sons, America, you murdered my own.”

Ultimately, the landays demonstrate the irrepressibility of the human spirit.

- Karin Ronnow, CAI’s communications director

August 19, 2013: A message from CAI Co-founder Greg Mortenson on World Humanitarian Day

Central Asia Institute today joins the global community in celebrating World Humanitarian Day.

We especially remember and give thanks for the humanitarians and aid workers, who have given their lives in the service of our fellow human beings.

The idea to have a World Humanitarian Day, and the month-long observation that follows, began after the tragic Aug. 19, 2003, murders of 22 aid workers at the United Nations office in Baghdad, Iraq. The goal is to increase awareness of the dedicated people, organizations, and communities that help people in distress due to disaster, exploitation, and neglect.

In 2008, there were more than 210,000 humanitarians working around the world, according to the Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance. However, in my opinion, there are actually millions of men and women who are dedicated to the service of others and hope to make the world a better place, including teachers, healthcare workers, human-rights activists, social workers, environmental activists, mediators, and volunteers.

Most humanitarians are passionate about their work, and feel it is a labor of love, or a calling, rather than a mere job. And in some parts of the world, dedicated humanitarians put their lives on the line in their service of others.

Although the news media often covers the murders of professional aid and development workers, many more humanitarians die in relative obscurity. Their poignant stories – especially those of the women in Afghanistan and Pakistan –resonate in my heart today, and I want to share a few with you.

In 2007, Zakia Zaki, the founder of “Radio Solha” or “Radio Peace” in Afghanistan’s Parwan province was killed in her bed at night, along with her 2-year-old daughter. Zakia, who was also a primary school principal, used the radio, which is often the only form of media in rural areas, to highlight violence and oppression against women, which put her on top of the Taliban’s hit list.

A year later, Belqis Mazlomyar, a female activist who helped empower Afghan refugee women through literacy, micro-credit and other programs, was killed by her stepbrother. Belqis was working in Nangarhar province, near the Pakistan border, and had continued her work despite death threats from men and religious leaders who were opposed to her assistance for widows and single mothers. Although her five children were devastated when Belqis was killed, her youngest daughter has resolved to follow her mother’s path and also be a humanitarian worker.

Hanifa Safi, a 51-year old human rights activist, was killed in Afghanistan’s Laghman province in July 2012, when the Taliban exploded an improvised bomb under the hood of her car. Her crime, according to the Taliban, was that she did not stay home and be a good wife, and instead became a public official, providing legal advocacy for female victims of domestic violence and abuse.

Sima Akakhel, a young girls’ school principal at Ahmad Shah Durrani Girls’ High School in Afghanistan’s Balkh province, was brutally murdered in her home on Aug. 10, 2012 during the fasting month of Ramadan, while her husband and father were praying at a local mosque. She was a fierce advocate of girls’ education in rural areas who, despite constant threats and harassment, never stopped trying to get every girl possible into school.

In March this year, a girls’ schoolteacher, Shahnaz Nazli, 41, was shot dead in Shahkas, near the town of Jamrud in Pakistan’s Khyber tribal district, between the northwestern city of Peshawar and the Afghan border. Despite having a low salary, and despite repeated family requests for her to stop teaching, Shahnaz had a strong conviction that her life’s calling was to teach. She paid with her life.

In May 2013, women’s activist and politician Zahra Hussain, 67,was shot in the face and killed by drive-by assailants as she left her home in Karachi, Pakistan. Zahra encouraged women to assert their legal rights and be more politically active and she was also outspoken about election rigging, which was most likely why she was murdered.

In June 2013, five women administering polio vaccines were gunned down in Karachi and Peshawar, Pakistan. Over the past decade, there has been a huge global push to eliminate polio, which has been a top priority of the Rotary Club. However, the Taliban attacks on polio workers, which began in 2012 and are part of their campaign to stop polio vaccines for good, have now exposed about 400,000 children in rural Pakistan and Afghanistan to polio.

Shamim Akhter, 50, a social worker from Hyderabad, Pakistan, who worked for the NGO Tando Jam, was also brutally murdered in June. Local police have refused to investigate and have threatened to kill her sister, Tasleem, if the family does not retract the investigation request.

These women represent just a fraction of the hundreds, if not thousands, of women who have been murdered around the world for simply trying to teach girls, alleviate suffering, empower the oppressed, and make the world a better place.

May we not forget their stories, yet remember that all of them would not want us to mourn or pause too long in memory, as there is still much work to do.

QUOTE: Tragedy is a tool for the living to gain wisdom, not a guide by which to live. – Robert Kennedy

- Greg Mortenson

August 16, 2013: YMCA campers get glimpse of life in remote villages where CAI works

BOZEMAN, Mont. — Start with breakfast. That’s what I did this week to help explain some of the similarities and differences between growing up here and growing up in the remote mountain villages where Central Asia Institute (CAI) works.

So what do campers at the YMCA Summer Adventure Camp eat for breakfast? Lots of cold cereal, they told me. One of them, however, prefers “chocolate toast” (toasted bread with Nutella spread). Another likes pizza.

But in Chapursan Valley, in the mountains of northern Pakistan where CAI has about two-dozen projects, a typical breakfast is bread and milk tea, I told them. And often, it’s the same for lunch and dinner.

“What if you don’t like bread and milk tea?” one camper asked, her eyebrows furrowed with concern.

“You eat it anyway because that’s all there is,” I said.

The YMCA camp emphasizes “fun and educational learning” for kindergarteners to sixth-graders. Each week counselors and campers focus on a theme and CAI was asked to participate in this week’s “Globetrotters” program.

The 45 students tried on hats from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. A couple of them walked slowly across the SOB Barn loft’s dusty wooden floor wearing a burka. And they asked dozens of questions about what daily life for the children we work with half a world away.

I told them about the class of high-school students I met this summer in Afghanistan who had never, ever ridden in a car or seen a computer; about the students in CAI-supported schools who wind up teaching their parents how to read; and about the comparatively small mud-brick houses, heated with smoky wood or dung fires, where extended families live and eat and sleep together.

“But kids are kids,” I said. “You and the children in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan are actually more alike than you are different. You all have families who love you and want the best for you and your future. And all around the world, a brighter future begins with education.”

A large part of CAI’s mission is to promote peace through education — in the communities where we work overseas, and just down the street.

QUOTE: Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all. – Aristotle

- Karin Ronnow with photos by CAI Database Manager, Laura Brin

|

|

Central Asia Institute’s Board of Directors and staff wish all our Muslim friends blessings of peace on Eid al-Fitr, at the conclusion of Ramadan.

Eid al-Fitr, which means “Festival of Breaking the Fast,” is one of the most joyous days in the Islamic calendar, marking the end of Ramadan, the Muslim holy month of fasting. It is in some ways similar in spirit to Christmas, Hannukah, Dewali, Kwanza and other faiths’ joyous occasions.

Throughout the month preceding Eid, the estimated 1.6 billion Muslims around the world focus on fasting (no food or water) during daylight hours, prayer, and charity. These are all demonstrations of self-sacrifice and devotion to Allah, or God.

“Ramadan marks the first revelation of the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad and is a time of increased spiritual reflection and devotion,” according to the Pew Research Center.

Ramadan holds special significance for Muslims, said Farid Senzai, a CAI board member.

“Its many benefits include that it allows Muslims to obey one of the major pillars of Islam and commandments from God,” Senzai said. “It also includes personal and spiritual purification as well as controlling one’s desires. It encourages empathy toward the poor and needy who do not have enough to eat or drink. And it creates a social dimension that brings Muslims from all walks of life together.”

Ramadan takes place during the ninth month on the Muslim lunar calendar, so Eid al-Fitr marks the start of the 10th month, Shawwal. As with Ramadan’s starting date, the ending date varies around the world depending on the sighting of the new, or crescent, moon.

“Some celebrate in conjunction with the local moon sighting,” CAI co-founder Greg Mortenson explained. “Others rely on the moon sighting in Saudi Arabia.”

Moon sightings are serious business when it comes to Ramadan. In Saudi Arabia, the Supreme Court collects evidence of crescent moon sightings, which this year were reported on Wednesday, Aug. 7, so Eid al-Fitr will be observed today, Aug. 8, in the kingdom.

In Pakistan, the Ruet-e-Hilal Committee, an elite body charged with moon sighting, is expected to sight the crescent moon tonight, with Eid celebrations on Friday.

At the end of a month of reflection and self-sacrifice, Eid is a time of thanksgiving. In the words of some CAI overseas managers who sent their best wishes by phone and e-mail today:

From the Hindu Kush Mountains in the Wakhan Corridor, Afghanistan: Wakhan manager, CAI community manager Pariwash (Pari) Gouhari: “Eid Mubarak to all our CAI supporters from all over the world who given us the best Idi [gifts given during Eid-al-Fitr] of all: schools and girls’ education through all the Wakhan.”

From the plains of Punjab Province in Pakistan, Suleman Minhas, CAI Punjab program manager: “Eid Mubarak to all people, and we pray for peace for all the world. We especially thank Dr. Greg and CAI team for 20 years of service to remote villagers, and the donors who give us the gift of education. Ramadan is a time we especially remember and pray for the poor people, widows, and orphans, and we open our hearts and make alms [charity] for the ones who suffer.”

From the Karakoram Mountains in Baltistan, northern Pakistan, CAI program manager Mohammad Nazir: “On this celebration of Eid, I send greetings from the CAI Baltistan team, and we give thanks to Allah for giving us life, health, family, and education. It is a happy time to celebrate and share gifts, but most of all we are grateful for education for the children, which gives us hope and peace for the future.”

From Kabul, the Afghan capital in the Hindu Kush Mountains, CAI-Afghanistan Program Manager Wakil Karimi: “On behalf of all CAI students and teachers here, my family and entire CAI Afghanistan team send greetings and best wishes to all of you who support CAI and education. The gift of education to the poor is the most precious and holy gift anyone can give and it gives us a future of hope and peace. Peace is very important to everybody, but especially to parents in Afghanistan who everyday worry about whether their children will return home from school or be injured or killed in suicide bomb, roadside bomb, shooting or poisoning. Thank you, Tashakur, for your belief in a better future for Afghanistan.”

And last but not least, from the Rocky Mountains of the United States, Greg Mortenson: “Eid Mubarak to all our Muslim friends, brothers and sisters, and thanks to the dear children, parents, teachers, and elders of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan for your patience, and teaching me about life’s greatest lessons. My life’s greatest honor is to serve you, support girls’ education, and be welcomed into your families with eternal hospitality and kindness.”

- Karin Ronnow, CAI communications director

August 7, 2013: CAI helps young Afghan women jump hurdles to higher education

NOTE: The young women’s names have been changed for their protection.

Every time I visit the Central Asia Institute-supported scholarship students attending university in Kabul, I am impressed by their determination, courage and persistence. They face a combination of obstacles most Westerners can barely fathom: life in a war-torn country, illiterate parents, an oppressive culture, entrenched poverty, and few female role models.

They are pioneers in their families and their communities. Yet they are modest about their accomplishments. They put their lives on the line every time they agree to share their stories. And their goals almost always revolve around making Afghanistan a better country.

“My decision for my future is to be a good teacher, serve my country, and [convey] those things that I learned to others,” 21-year-old Fahima, a CAI-supported student who attends a teacher’s college in Kapisa Province, said recently. “My parents are not educated people. And they are very interested that I study more and more to become a very famous person and do service to my country.”

The country needs educated young adults. Nearly 75 percent of the Afghan population is illiterate; 88 percent of women are unable to read and write, according to a UN Report.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. “Despite the progress of the past few years, Afghanistan is extremely poor, landlocked, and highly dependent on foreign aid,” according to Index Mundi. “Much of the population continues to suffer from shortages of housing, clean water, electricity, medical care, and jobs. …. Afghanistan’s living standards are among the lowest in the world.”

CAI believes education is fundamental to a better future for Afghanistan – and Afghans agree. “Demand among Afghans for better schooling … is at its highest point in decades,” New York Times reported July 20.

Enormous barriers still exist. An estimated 4.2 million children, mostly girls, still don’t attend school. Of those girls who do enroll, many drop out before reaching high school due to forced marriage, a shortage of female teachers, conservative beliefs that girls should not study or work outside the home, or security concerns amid Taliban threats. If they do manage to finish high school, girls who want to attend university still must take and pass the university entrance exam, the kankor, get permission from their parents to attend university, and find a way to finance it.

It’s easy to see why only one-fourth of the students in Afghanistan’s universities are female.

On the other hand, the good news is women make up 25 percent of university students, and that their numbers have been growing steadily since the Taliban government was ousted in 2001, according to the UN report on Afghanistan’s compliance with the UN Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.

In any given academic year, CAI supports 18 to 20 young Afghan women pursuing college and university degrees. Those girls know they are among the lucky ones. Education has changed them – for the better.

“My childhood has been different because of my education,” said Aliah, 20, also a student at the Kapisa college. “I enjoy every second of my life. I guess that I am a complete person.”

* * * *

Here are some thoughts from these and other CAI scholars’ about the importance of education and their dreams for the future:

Why is education important?

Hila, 20, Kabul Medical University: “Education is important because it is the light in our lives that helps us find our way to a good life, security, and a good economic situation for our families.”

Karimah, 24, Kapisa: “With knowledge we can know the difference between good and bad, do our duties, and arrange our lives in successful ways”

Latifa, 19, Kapisa: “Education is important because it makes us better citizens and we can be better people.”

Aliah: “Learning makes our future bright. Also, by knowledge we can know ourselves and our God. Knowledge is like a big ocean. And today the cause of the world is the promotion of education.”

Fahima: “Education is important because it is the message of Islamic religion and the basis of civil society.”

Laila, 26, Kabul: “It is important because it is our duty to learn knowledge, serve our country and the children and eliminate the ignorance from our country.”

Niazmina, 22, Kapisa: “Knowledge is the bridge between the lightness and the darkness in our lives.”

Dreams for future

Karimah: “I want to be a good teacher to serve my country and have knowledgeable people to bring peace in our nice country.”

Hila: “I hope to be a wonderful doctor for my people.”

Latifa: “My decision for my future life is to be a good teacher and serve the kind children of my country.”

Sherina, 21: “The most important thing is to provide access to education so that [Afghans] can learn something and do it in our practical life. Then, lots of changes will come, we can build our society and improve our own lives.

Niazmina: “I want to be able to make money so that I can help myself, my parents and family and my country.”

How is your life different because you have an education?

Sherina: “When I learn knowledge, at first I know myself, and then I know my God. I also know about my responsibility to respect my nice parents. And from the time that I started education my life became a bonanza. I become successful in all that I do. I am thankful to my kind Allah that give me the chance to study and become a literate person. … By learning knowledge we can build our society.”

Fahima: “Knowledge brings the positive points in my life and I am happy that I have education.”

Latifa: “Lots of changes have happened in my life because of education. It means we can know about events that happened [history] and what is going on now in the world. And education teaches us to respect our parents and elders.”

Niazmina: “A lot changed when knowledge came into my life. They were positive changes. I better understand my relations with my family and other people. And I learned that, without knowledge, life is like a dark ocean and we can’t find or get to our target. With education we have a secure society, money and peace – [all of which help us] get to our target.”

Hila: “My education makes me a more successful person.”

Laila: “When a person gets education the positive changes come into their lives. From the time that I started learning, lots of changes came into my life. I can make decisions with my whole family. Also, with learning comes opportunities to make money and without money we can’t do anything.”

QUOTE: A good head and good heart are always a formidable combination. But when you add to that a literate tongue or pen, then you have something very special. – Nelson Mandela

- Karin Ronnow, with help from Wakil Karimi in Kabul

July 23, 2013: Silver Jubilee party marks 20 years working in Baltistan

When Greg and CAI Executive Director David Starnes arrived in Skardu in mid-June this year, CAI’s local program director, Mohammad Nazir, had a surprise waiting: The traditional welcoming tea had ballooned into a party with more than a dozen old friends.

“Today is the 20th anniversary of ‘Dr. Greg’s’ mission” to promote education in the mountain villages of Pakistan, Nazir said. “He came in 1993 to climb K2. So this is the Silver Jubilee.”

“Twenty years of service,” he added, then waved his arm to indicate the cake and a table laden with sweets and fresh fruit, tea and cold drinks. “Congratulations, sir!”

Greg, who is still fondly referred to as “Dr. Greg” in this region, introduced David to the people who had gathered to welcome them and then took a few moments to greet his friends individually.

Before cutting the cake, he asked Apo Abdul Razak, his long-time friend and colleague, to say a dua (prayer).

As everyone sat down, Greg and his friends recalled when he came to Baltistan in 1993 to climb K2, the world’s second-highest mountain. Over the next few years, he returned several times as he worked to fulfill his dream to build a school. By 1996, he and the villagers of Korphe, with financial help from the American Himalayan Foundation, had finished the first school ever built in that community. That year he also formed the nonprofit Central Asia Institute (CAI) with help from CAI cofounder Jean Hoerni.

When asked what has changed in the intervening years, Nazir said, “Every year is an adventure, with new things. These days much has changed with the people understanding the importance of education, especially for their sisters and daughters. Now they understand everything, and Baltistan is stronger because of CAI and Greg’s work.”

Greg, who grew up on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania, where his late father helped establish Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center, has always said that real change takes one or two generations, and referred to an old Swahili proverb: “The gestation of an elephant takes longer than that of a goat,” which means good things take a while to manifest.

“It is rewarding and inspiring to see that some of the first girls to go in our schools are now mothers, college graduates, and, even more, that they are making a profound change in the community,” Greg said.

At one point during the afternoon party, Nazir took a moment to acknowledge the past.

“The only thing missing is our old friends and teachers, but they are with us in spirit,” he said, referring to former colleagues who have died, including Haji Ali, the former village leader in Korphe, and Sarfraz Khan, CAI’s most-remote-areas project manager, who died of cancer last November.

“For us, Greg is still the same,” Nazir said, smiling. “We feel like we did in the beginning – we have hope and we are very thankful he came to Baltistan.”

QUOTE: Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has. – Margaret Mead

- Karin Ronnow, CAI communications director

June 4, 2013: CAI team visits Broghil region of extreme northern Pakistan

GILGIT, Pakistan – Central Asia Institute’s Gilgit-based team, photographer Erik Petersen, and I have just returned from an amazing journey to visit some of CAI’s projects in the Broghil region of extreme northern Pakistan, adjacent to the Wakhan corridor of Afghanistan. These projects are some of CAI’s most remote undertakings in Pakistan, difficult to access, and beyond range of roads, phones, or electricity.

The Broghil region is one of the most underserved areas in Pakistan, with few schools or educational opportunities. The people eke out a living in a barren environment at high altitude (often over 10,000 ft), and are blocked off from civilization for about 7-8 months annually due to harsh winters. In addition to their livestock of sheep, goats, and yaks, they are agro-pasturalists, who live on marginal subsistence crops of potatoes, buckwheat, and barley.

Originally, people migrated here to escape wars, natural disasters, slavery, high taxation, and persecution. To escape the long winters, and due to lack of health care, opium addiction has been historically rampant here, although recent health care initiatives have had an impact.

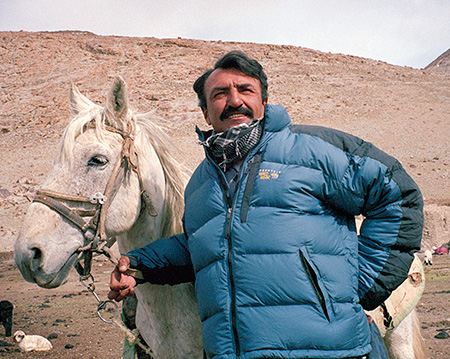

We traveled by jeep, foot, and horseback through the Hindu Kush Mountains to Broghil, where CAI has two schools and supports a third. Our ultimate destination was Chilmarabad High School, about 3 miles from the Afghanistan border. Along the way, we received remarkable hospitality, even though the villagers had little to spare, and they were grateful that an NGO has taken an interest in their plight and future.

Erik and I were the first foreigners in five years to travel the route, an ancient trade route that was closed by the Pakistan government, but reopened this spring at CAI’s request with the help of Pakistan’s intelligence services, military, and former Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Chief Minister Ameer Haider Khan Hoti.

Besides the sheer spectacle of traveling on horseback under blue skies into such a pristine area, amidst the chatter of marmots, the highlight of the trip was to meet the eager students and dedicated teachers, who see education as their greatest hope and tool to improve their lives for the future.

Here are some of Erik’s photos from our journey:

Fazil Baig, left, CAI’s Ghizer-area program manager, CAI

Communications Director Karin Ronnow, and Iqbal Karim, CAI-Gilgit accountant, ride

along an old trade route en route to Chilmarabad School, high in the Hindu Kush, an

eight-hour round-trip hike or horseback ride from the end of the road. Photo: Erik

Petersen, 2013.

|

Chilmarabad students and staff pose for a photo outside the

school, which was completed in 2012. Photo: Erik Petersen, 2013.

|

A goat herder moves her flock past laborers, at bottom, as

they break ground on the new Gharan School in northern Pakistan. Photo: Erik

Petersen, 2013.

|

On the trip back to Gilgit, the CAI team came around a corner

on the infrequently traveled road to find a crowd of residents of Khand Khun, who